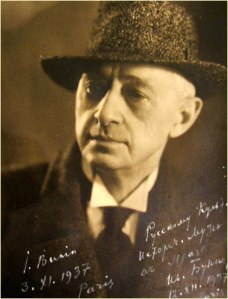

Ivan Bunin’s Dark Avenues has been on my bookshelf since I requested it as a Christmas present last year. Why I had asked for it, where I’d heard about Bunin and what I’d heard about Bunin are questions that slip merrily through the sieve of my memory. We undoubtedly all have these forgotten books on our shelves – I know I have many more! – and it was intriguing to pluck Dark Avenues out and read these marvellous stories, wondering where the bloody hell I had found out about this great author. I guess I’ll never know, but I am thankful to my former self for putting Bunin on my bookshelf.

A collection of 38 stories plus additional material, notes and appendices, Dark Avenues, I think, gives you a good grounding on what Bunin is all about as a writer. His tales can be sporadic and the collection takes you across the continent, through a dark, sprawling Russia onto neighbouring Ukraine, onwards towards Austria, Italy, Paris, the South of France and as far west as Madrid. They say variety is the spice of life, but I’d say that the spice of Dark Avenues is in what remains constant. The beauty of Bunin’s prose, for me, lies in his attention to detail, his ability to evoke landscapes, characters, emotions, actions, all of which he does with an astounding efficiency and charm. Each story is a microcosm contained within itself which sucks the reader in. There were so many times I got to the end of a story and felt like I knew the characters fairly well, I empathised with them, I had breathed the air of their landscape. But then I’d flick back to the beginning and realise that the story was only 1, 2 or 3 pages long. Bunin has this magical way of writing with such clarity, purpose and efficiency that he is able to portray so much information in a scarily short amount of space. If you are engaged in the narrative you might not really notice it, but once I’d cottoned on to his terseness I begin to look more meticulously at the mechanics of his language. And it is often at the beginning of his stories where a lot of the magic comes to life. In one or two paragraphs Bunin (and credit to the translator here for translating this quality into English!) will set the scene, the characters, and their backgrounds, only including information that the reader will need at some point in the story. He will never use too many characters, describe something in too much detail or indeed describe something at all if it is unnecessary.

I particularly enjoyed Bunin’s characters, who are typically peculiar, mysterious but essentially interesting to read about. He has a deep fascination with youth and young love, one of the unifying motifs of Dark Avenues. Several of his stories depict the first seeds of a relationship, or a love encounter between two characters. They are often physical, sensual passages and it is the universality of this theme that will allow Bunin’s stories appeal to a large audience. I think we all remember our first kiss, our first sexual encounter, our first relationship with a certain affection, often as defining moments in our young adult lives, and you can understand why Bunin may be interested by this period in his characters’ lives. In fact, many YA and indeed adult authors write about these periods in their characters’ lives as they develop from naïve adolescents into adults. Think Harry Potter, The Fault in our Stars, Twilight or many more YA hits that have been piled high in bookshops in recent years. Before this all goes a bit pear-shaped, I am not trying to categorise Ivan Bunin as a YA author alongside Stephanie Meyer and John Green, but it is fascinating to consider how this early 20th century Russian Nobel Prize for Literature winning master was drawing on his characters’ younger years to engage his reader just as many YA authors do today.

Another aspect of Dark Avenues I adored was its insight into Russian culture. Proceed through the stories, you are given a flavour of the period and the culture with the samovars, the dark, expansive, brooding landscape, the strange-sounding soups, inevitable vodka, the old carriage trains and chilling Eastern climate. The beauty of young Russian ladies is frequently apparent, with Bunin often conveying the almost ‘translucent’ paleness of their skin juxtaposed with the smooth, shining black darkness of their eyebrows and hair. In fact, Nabokov famously called Bunin a ‘connoisseur of colours’ and it is true that Bunin frequently draws on colour in his stories with aplomb, another feature which gives his work its vivid, ‘colourful’ aspect. Bunin is a masterful writer who works with the precision of a poet, and I would urge every writer, and especially short story writers, to study the mechanics of Bunin’s stories as a model for how to write a successful, purposeful short story. I will certainly be revisiting this collection in the past and look forward to exploring his other works. If you would recommend any, I would love to hear from you!